Dancing on the Ceiling: Art & Zero Gravity

BY KATHLEEN FORDE

The words “gravity” and “gravitas” share a common etymology, both originating in the Latin for weight or heaviness. Gravity is the physical force of attraction between massive objects, but it also connotes seriousness and depth, a metaphorical weight. Scientists speak of zero gravity, microgravity, and reduced gravity, states in which the physical force of gravity is diminished, limited, or even suspended. These states are characterized by the subjective experience of lightness or weightlessness.

If gravity is another word for seriousness, lightness connotes levity and freedom from care. In his collection of lectures, Six Memos for the New Millennium, the Italian writer Italo Calvino observes, “There is such a thing as a lightness of thoughtfulness, just as we all know there is a lightness of frivolity. In fact, thoughtful lightness can make frivolity seem dull and heavy.”1

Thoughtful lightness is the common denominator of the work in Dancing on the Ceiling: Art & Zero Gravity. The artists represented in this exhibition explore—and on occasion create—the condition of weightlessness on earth, using photography, sculpture, installation, film, and video. Their pieces feature floating performers, a public flotation tank, and skateboarders who flout the laws of physics. They evoke the golden age of space exploration and the dreams of the counter-culture. All of the work is thoughtful, layered, and ultimately quite weighty indeed. Distributed throughout the public spaces at EMPAC, the exhibition is itself untethered from the confines of the traditional gallery paradigm.

Although the artworks in Dancing on the Ceiling are diverse, the exhibition as a whole is informed by two primary conceits. The first is a broad exploration of the metaphorical theme of transcendence. The second is the actual use of zero gravity, or something that looks very much like it, to evoke the force of gravity itself, which humans may attempt to defy but can never wholly escape. Most of the artists move toward one or the other of these ideas. Some hover between them.

In Kantian philosophy, transcendence is a psychological experience that lies beyond the limits of ordinary reality and may even extend those limits. Several of the artists in this show seem to identify transcendence with the

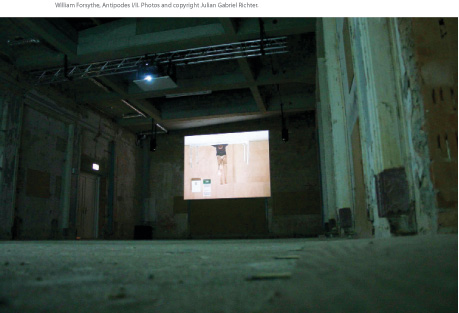

agility of a mind freed from entrenched perspectives. The two videos that make up William Forsythe’s Antipodes I/II, for example, track a dancer whose movements appear to counteract gravity while confounding our notions of physical space. In his new commission, Method Air, Chris Doyle seems to literally penetrate the

façade of a building with projections of animated skateboarders who fly weightlessly in and out of the structure.

In Kantian philosophy, transcendence is a psychological experience that lies beyond the limits of ordinary reality and may even extend those limits. Several of the artists in this show seem to identify transcendence with the

agility of a mind freed from entrenched perspectives. The two videos that make up William Forsythe’s Antipodes I/II, for example, track a dancer whose movements appear to counteract gravity while confounding our notions of physical space. In his new commission, Method Air, Chris Doyle seems to literally penetrate the

façade of a building with projections of animated skateboarders who fly weightlessly in and out of the structure.

Like Doyle, Jane and Louise Wilson also explore transcendence and its relationship to architecture and place. In their four-channel video installation, Stasi City, the British artists (and twins) conduct an investigation of the former headquarters of the East German secret police that culminates in an image of escape from unbearable psychological stress. In two double-wall projections, we see a camera panning quickly around the deserted space, revealing its hidden offices and suggesting what once transpired in them. The camera’s movements recall the surveillance that was the building’s principal enterprise in its former existence. In the last section of the film, we see the feet of a floating figure, a dramatic evocation of the route taken by unnumbered people who, unable to physically escape Stasi City, fled in their imagination.

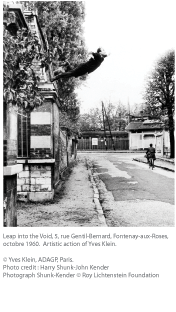

If we go beyond a purely philosophical reading and examine these works in an art-historical context, we find that many of their artists seem to recall the Dada movement of the early 20th century, which embraced irrationality as a vehicle for anti-war politics and a rejection of

artistic standards. Yves Klein’s well-known 1960 photomontage, Leap into the Void: The Painter of Space Throws Himself into the Void!, clearly belongs to the Dada tradition. The piece, which depicts the artist jumping off a wall toward the pavement with arms outstretched, is an expression of the will to transcend boundaries that runs through Klein’s entire oeuvre.

If we go beyond a purely philosophical reading and examine these works in an art-historical context, we find that many of their artists seem to recall the Dada movement of the early 20th century, which embraced irrationality as a vehicle for anti-war politics and a rejection of

artistic standards. Yves Klein’s well-known 1960 photomontage, Leap into the Void: The Painter of Space Throws Himself into the Void!, clearly belongs to the Dada tradition. The piece, which depicts the artist jumping off a wall toward the pavement with arms outstretched, is an expression of the will to transcend boundaries that runs through Klein’s entire oeuvre.

German artist Thom Kubli draws inspiration from both Klein and scientist John Lilly for his new commission, Float! The installation invites the viewer to experience a session in a flotation tank. The one Kubli uses is descended from Lilly’s invention of 1954, a tub-like enclosure designed for a single occupant, who would float inside in complete darkness, immersed in salt water at body temperature. The water’s high salinity makes bodies immersed in it more buoyant, a phenomenon familiar to anyone who has swum in the Dead Sea. Lilly used these tanks in the research he conducted for NASA into the effects of reduced sensory stimulation. His interest in expanding the mind’s powers also led to professional and personal experiments involving meditation and the use of LSD, both in and out of the flotation tank.

Prior to the opening of the exhibition, Kubli spent time floating in the tank and transcribing his thoughts immediately afterward, then adapting these writings into political speeches. Gallery visitors can hear Kubli’s reduced-gravity-inspired discourses or even take a dip in the tank themselves while listening to a soundtrack composed by the artist. For Kubli, the intent of the piece is to create what he calls an “anti-environment,” a physical experience that stands in radical contradiction to those we encounter in everyday life, where we feel the tug of gravity and spend most of our time on dry land. “It is the difference,” he believes, “that provokes us to experience a view of our environment that is normally imperceptible to us. Therefore, a space as dedicated to individualism and isolation as the samadhi-tank could conceal an ambiguous political potential.“

In The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984), Milan Kundera considers the insignificance of the individual lifetime in light of the Nietzschean concept of eternal return. In an infinite universe, where everything is guaranteed to recur again and again, a single life is small and devoid of meaning. Alongside the aforementioned pieces that use zero gravity as a metaphor for the human impulse to reach beyond our present reality are works that produce a real —if temporary—escape from gravity to remind us that gravity is ultimately inescapable. These works have the additional effect of compelling us to rethink our customary relationship to space and time.

In Ground Control, artist Edith Dekyndt places a black ball filled with a mixture of helium and oxygen in the public space of the exhibition, where it hovers, unsupported by rigging devices or stands. However, the ratio between the two gases must be continuously and precisely regulated for the ball to remain “alive.” Without such attention, gravity gains the upper hand and the piece begins to sink. In 59 Steps to be on Air by Sun Power/Do it Yourself, Tomás Saraceno literally provides viewers with instructions for flying by means of a geodesic solar balloon. Drawings illustrating how to build the device are distributed throughout the space to be taken away by visitors.

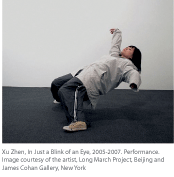

Xu Zhen’s In Just a Blink of the Eye uses performers who are held precariously upright by concealed braces so that they appear to be suspended in the exhibition space in defiance of both gravity and time. They look like they are on the verge of falling, but they do not fall, and their stasis makes the relationship of time to space almost physically concrete. Time becomes an architectural space frozen within, and set apart from, “normal” human chronology. The performers seem to have broken free from the linear trajectory of life, with its continuous path of sequential goals, responsibilities, gains, and losses from birth to death. The defiance of gravity in Xu Zhen’s piece is mind-boggling. At the same time, we know that his actors will eventually sink to earth, a somewhat depressing counterpoint to the catharsis of their suspension.

Xu Zhen’s In Just a Blink of the Eye uses performers who are held precariously upright by concealed braces so that they appear to be suspended in the exhibition space in defiance of both gravity and time. They look like they are on the verge of falling, but they do not fall, and their stasis makes the relationship of time to space almost physically concrete. Time becomes an architectural space frozen within, and set apart from, “normal” human chronology. The performers seem to have broken free from the linear trajectory of life, with its continuous path of sequential goals, responsibilities, gains, and losses from birth to death. The defiance of gravity in Xu Zhen’s piece is mind-boggling. At the same time, we know that his actors will eventually sink to earth, a somewhat depressing counterpoint to the catharsis of their suspension.

Denis Darzacq also explores frozen moments in his series The Fall. For these photographs, Darzacq worked with young Parisian hip-hop dancers in banal urban environments and shot them in mid-leap, just before they hit the pavement. The result is an intense collection of still images that paradoxically explore motion. They also have a zen-like quality that suggests an attempt to grasp a moment and truly explore its temporality, its physicality, and its energy.

Darzaq worked on this series shortly after the 2005 riots in Paris. Viewed in this context, The Fall seems to call attention to the space between serenity and turbulence. Although Darzaq is known to encourage multiple readings of the work, he has suggested that in this piece he is particularly thinking about a generation of young French people who have been ignored by their society, which has abandoned them in a state of free-fall.

Considered as a totality, the work in Dancing on the Ceiling raises the question of just why so many artists are exploring the theme of weightlessness at this time. For some artists working in this vein, the answer could simply be because they can. The UK-based

commissioning body, the Arts Catalyst, for instance, is currently subsidizing artists and scientists to take actual parabolic flights in specially modified aircraft and filming the resulting interval of zero gravity as research and content for performances and installations. Other artists, exploiting new technology, use complex digital effects or computerized rigging to create the illusion of weightlessness. However, just as many artists are using traditional methods to realize their ideas.

Considered as a totality, the work in Dancing on the Ceiling raises the question of just why so many artists are exploring the theme of weightlessness at this time. For some artists working in this vein, the answer could simply be because they can. The UK-based

commissioning body, the Arts Catalyst, for instance, is currently subsidizing artists and scientists to take actual parabolic flights in specially modified aircraft and filming the resulting interval of zero gravity as research and content for performances and installations. Other artists, exploiting new technology, use complex digital effects or computerized rigging to create the illusion of weightlessness. However, just as many artists are using traditional methods to realize their ideas.

At the core of their intentions lie not just the techniques of visualizing weightlessness, but the metaphors that arise from that visualization. Given the current state of a world at war and in massive economic and ecological distress, it is not surprising that notions of transcendence, lightness, and the re-contextualization of physical and political perspectives are so prevalent. This strategy has been at play throughout history. Particularly in the modern era, artists and thinkers have deployed radical shifts of perspective in order to explore the landscape of their time. One need only look at Freud’s uncanny, Marshall McCluhan’s counter-space, or Gaston Bachelard’s anti-environment for antecedents. The constant is that contemporary artists and philosophers continue to provoke their audience to look at the world through a completely different lens. The work in this show ranges in tone from playful to serious, magical to practical, defiant to serene. The artists deploy helium, parabolic flight, flotation, rigging, and digital effects to carry out their conceptual motivations. Yet every artist pushes us to think about the world we live in, the ground we stand on, and to reimagine the physical and psychological reality we previously thought of as fixed and binding as something more flexible, mutable, and light. –KF